I recently acquired a 1969 Goya guitar that needed a neck reset. Goya guitars were rebranded Levins sold in North America by an importer. Levin was a respected Swedish guitar manufacturer, established in 1908. Goya eventually became nothing more than a label, and as far as I know they no longer exist, but Martin still owns the trademark. The Levin company is gone too, and so Levins and Goyas are now “vintage collectibles”, whatever that means.

Their biggest claim to fame in my understanding is the famous photograph of Django smoking a cigarette, with a Levin archtop guitar up under his chin.

I fixed the neck on the Goya, and soon realized that despite the fact that it was made of first quality materials, it had a very low-grade tone. This was a surprise, as I assumed that it would sound great, being well constructed of fine solid woods, and fitted with a standard X braced top and all. But alas, it was loud, extremely shrill, and lacking even a decent amount of bass and mid-range.

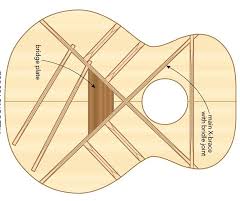

What to do? I got my small bronze luthier/violinmaker’s plane and proceeded to shave wood from all the braces I could reach. I have done this on many guitars, so I knew it worked, but in this case, I had to remove a lot more wood than expected. What I could not reach with the tiny plane, I filed with the rough end of my 4 in one file. After each session I strung the guitar up and played it, and banged on the top with a small felt tipped wood hammer.

Tapping tells a lot about the responsiveness and pitch of the soundboard. What started out as sounding like a wooden desktop eventually began to open up and produce a much wider range of tones, especially in the lower frequencies. The decay time lengthened appreciably too. It took quite a few sessions, but eventually the guitar went from sounding like a banjo to sounding like a great guitar. This was very satisfying!

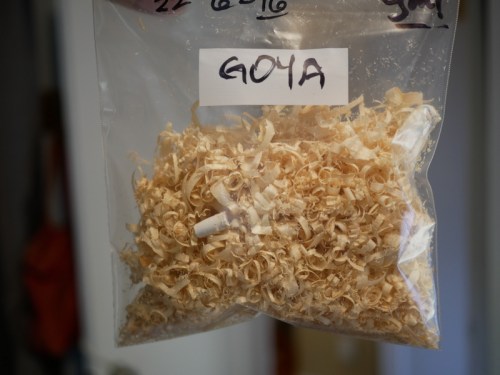

The shavings I collected weighed 16 grams. That may seem like nothing, but represents a significant proportion of the overall bracing weight. I did some calculations based on what I could see inside and estimated the total weight of the braces in the active zone at about 68 grams. Reducing the height of a brace has a rapid and strong effect on the stiffness, which determines the resonance. Engineering wise, when a beam is reduced in depth (height), it loses stiffness proportionally to the 3rd power.

If my guessing is accurate, the 16 grams of shavings removed represented 24% of the mass of all braces. I shaved down the main X braces, the tone bars that crossed the lower bout, and 4 short finger braces between the main X braces and the rim. The main X brace measured 17mm high at the crossing, and was reduced to around 15mm. I ramped the legs of the braces in both directions, taking more from the back end, as that is where the greatest effect happens. I did not attempt to scallop the braces, because in my opinion this is not the best idea in a case like this. Maybe it works when done before the guitar is built, but it doesn’t have enough effect when attempted on an overbuilt guitar like this one. In any case, ramped braces sound fine to my ears, and I find the frequency response of ramped braces very pleasing.

My rough estimating indicated that I reduced the stiffness of the top by about 60%. That is huge, yet it took that much reduction to get the guitar to sound good. One can only conclude that guitar makers tend to overbrace their tops. That doesn’t make for great guitars, which is why there are so many good guitars and only a few great ones! He who dares, wins…